Estimated reading time: 13 minutes

Harvesting and Selection

The initial steps in champagne production are critical as they set the foundation for the beverage’s quality. Your understanding of when and how the grapes are picked and the selection criteria will provide insight into the meticulous process behind Champagne creation.

Picking the Grapes

As you explore the process of champagne making, the harvesting stage demands attention to timing and technique. Grapes used in champagne, primarily Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, and Meunier, must be picked at their optimal ripeness. This is determined by the terroir – a French term encapsulating soil, topography, and climate – of the village where the grapes are grown. The time of harvest is crucial; it’s influenced by the local climate and is typically condensed into a frantic two-week period to ensure consistency and quality.

- Timing of Harvest: Often between late August and early October.

- Techniques: Grapes are picked by hand to preserve their integrity.

Choosing Grape Varieties

The selection of grape varieties is essential for the cuvee, the base wine for champagne. Each variety contributes unique characteristics to the cuvee:

- Chardonnay: Imparts finesse, lightness, and acidity.

- Pinot Noir: Adds structure and depth.

- Meunier: Offers fruitiness and freshness.

The choice of grapes is influenced by the desired vintage and marque of the champagne. Only grapes from classified and approved villages are selected, ensuring the quality and reputation of the champagne are upheld.

- Grape Variety Proportions: Varied depending on house style and vintage.

- Qualification: Strict adherence to appellation regulations.

Pressing and Juice Extraction

In the production of Champagne, obtaining the purest juice from the grapes is crucial to ensuring the quality and character of the final product. This process involves two main steps: gentle pressing to extract the juice and then allowing the juice to settle for clarification.

Gentle Pressing

When you begin making Champagne, you must select the appropriate grape varieties, which typically include Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, and Pinot Meunier. Pressing these grapes gently is essential to Champagne production, as it prevents the release of harsh compounds from the skins and seeds, which could affect the wine’s delicate taste. Traditionally, a Coquard press is used, which allows for a controlled and gradual increase in pressure. Your goal is to obtain the ‘cuvee,’ the first and most prized juice from the pressing, which is reserved for Champagne.

- Step 1: Sort and prepare grapes for pressing.

- Step 2: Place sorted grapes in the press.

- Step 3: Apply pressure gradually to extract the cuvee.

Settling and Clarification

After pressing, you need to allow the extracted juice to settle in a process known as débourbage or clarification. During this phase, solids such as grape skins and seeds that were inadvertently mixed with the juice during pressing will settle to the bottom. This settling usually occurs in temperature-controlled stainless steel tanks to facilitate the process.

- Duration: Typically 12-24 hours.

- Temperature: Kept cool to prevent premature fermentation.

- Result: Clearer juice that is ready for fermentation.

The clear juice, free from most solids, is then transferred to fermentation tanks, thus completing this vital step in your Champagne-making journey.

Primary Fermentation

Primary fermentation is the critical stage where the base wine for Champagne is created through the careful conversion of grape sugars into alcohol by yeast.

Creating the Base Wine

At this stage, you’ll find that cultured yeast strains, known for their ability to enhance the Champagne’s flavor profile, are added to the juice of pressed grapes in stainless-steel tanks. The yeast consumes the natural sugars present in the grape juice and converts them into alcohol and carbon dioxide through the fermentation process. This primary fermentation typically lasts for about two weeks and results in a still wine with about 10-11% alcohol by volume.

- Cultured Yeast Addition: Precision-selected for Champagne.

- Sugar Conversion: Yeast transforms sugars into alcohol and CO2.

- Duration: Roughly 14 days.

Malolactic Fermentation Optional

Malolactic fermentation is an optional process that may follow primary fermentation, depending on the winemaker’s style preference. By encouraging certain bacteria to convert harsher malic acid into smoother lactic acid, the resulting base wine acquires a rounder, buttery character.

- Process: Converts malic acid to lactic acid.

- Effect on Wine: Produces a smoother, less acidic profile.

Through these meticulous steps, the still wine develops the preliminary flavors that will be built upon in the subsequent stages of Champagne production.

Blending and Assemblage

Before the final champagne is bottled, an intricate blending and assemblage process is crucial. You’ll understand how producers meticulously combine wines from various vintages and create the cuvée, setting the foundation for the champagne’s unique character.

Combining Wines from Different Vintages

In the blending phase, reserve wines from previous years are artfully mixed with wines of the current vintage. This practice allows champagne houses to achieve a consistent house style, especially for non-vintage champagnes. By selecting and combining different vintages, producers can balance the flavors and ensure the complexity of the champagne’s profile. Your understanding of this step reveals how each champagne maintains its signature taste despite the annual variations in harvest.

- Non-vintage Champagne: A blend of multiple vintages, aimed at a consistent style.

- Vintage Champagne: Produced from grapes of a single year’s harvest, reflecting the particular characteristics of that year.

Creating the Cuvée

Creating the cuvée is the process of selecting specific wines to blend before the second fermentation, which carbonates the champagne. The cuvée represents the initial blend and typically includes a combination of wines from different vineyards, grape varieties, and vintage years. It’s your window into the craftsmanship of the champagne producers, who carefully orchestrate the blend to meet the house’s desired profile in both flavor and aroma.

- The Cuvée:

- Primary Role: To set the foundation for champagne’s flavor profile.

- Consists of: Selected wines from different vineyards and grape varieties.

By keeping these practices in mind, you can better appreciate the complexity and artistry involved in creating the unique and celebrated beverage that is champagne.

Secondary Fermentation and Maturation

In this stage, your champagne undergoes a transformation, where sugar and yeast are added to initiate secondary fermentation which creates the characteristic bubbles. The aging on lees then enhances the complexity of flavors.

Tirage and Addition of Liqueur de Tirage

To begin secondary fermentation, a mixture called liqueur de tirage—composed of sugar and yeast—is added to your bottled wine. This concoction triggers the fermentation process within the sealed environment of the bottle. This tirage mixture is crucial because it causes the wine to produce carbon dioxide and alcohol, which cannot escape, thus dissolving into the wine and forming the fine bubbles synonymous with sparkling wine.

Lees Aging and Formation of Bubbles

During the aging process, champagne bottles are stored horizontally, allowing the wine to age on its lees—the dead yeast cells. This aging period can last several years, contributing to the texture and flavors of the champagne. The lees also play a critical role in the formation of bubbles, helping to create the persistent fine mousse that distinguishes high-quality champagne.

Riddling Process

Riddling, or remuage, is a method used to consolidate the lees at the neck of the bottle. Traditionally performed by hand, bottles are turned periodically and gradually tilted using a riddling rack, resulting in the lees settling in the bottle’s neck. Once the riddling process is completed, the lees are removed, and the champagne is ready for the final steps before it can be enjoyed.

Disgorgement and Dosage

In the champagne-making process, disgorgement is a critical step where yeast sediment is removed, while dosage involves adjusting the sweetness level of the finished product.

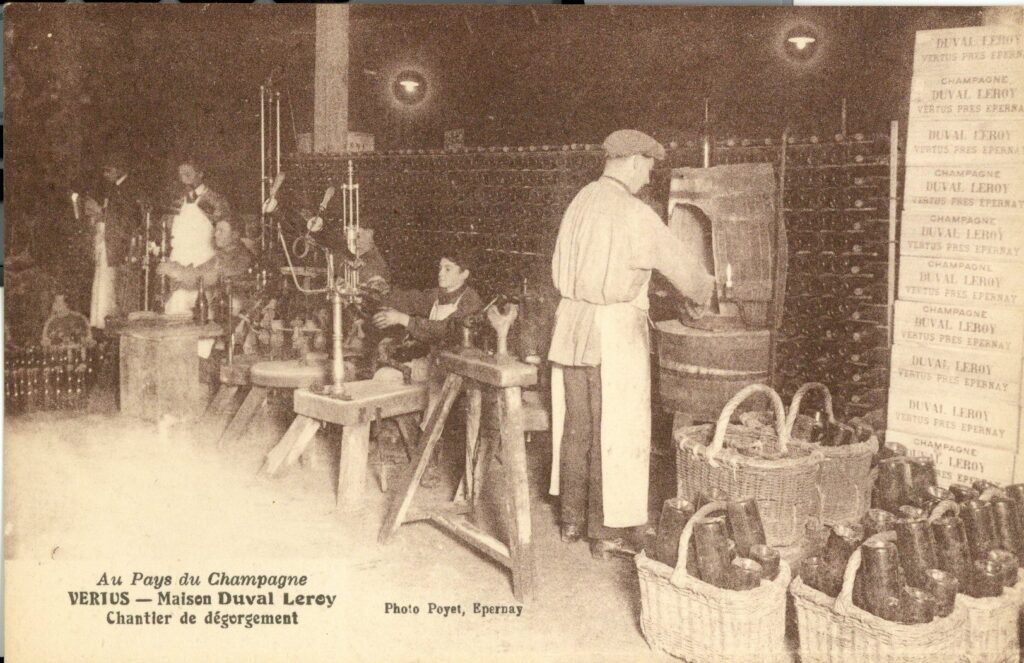

Expelling the Lees

Disgorgement (dégorgement) is the phase in which the sediment formed by the lees—dead yeast cells accumulated during fermentation—is expelled from the bottle. To prepare for this, champagne bottles undergo a process called riddling which gradually tilts and turns the bottle to encourage lees collection near the cork. Once the sediment is consolidated, the neck of the bottle is chilled, freezing the lees into a solid plug. Upon opening, the pressure inside forces the plug out, leaving the champagne clear.

- Chill neck of the bottle

- Open to expel frozen lees

- Ensure champagne clarity

Adjusting Sweetness Level

After disgorgement, the dosage step tailors the champagne’s sweetness. A liqueur d’expedition, a mixture of wine and sugar, is added. The amount determines the sweetness category of the champagne which ranges from brut nature (no added sugar) to doux (very sweet). Common categories include:

- Brut Nature: 0-3 g/l sugar

- Extra Brut: 0-6 g/l sugar

- Brut: less than 12 g/l sugar

- Extra Sec: 12-17 g/l sugar

- Sec: 17-32 g/l sugar

- Demi-Sec: 32-50 g/l sugar

- Doux: 50+ g/l sugar

Your champagne is then corked and secured, ready for final aging or sale.

Final Touches and Presentation

Once the champagne has matured, it’s time for the final touches that will ensure the bottles are ready to be presented and enjoyed. Proper corking and wiring are vital to maintain the sparkling wine’s integrity, while labeling and packaging are key to brand identity and consumer appeal.

Corking and Wiring

Corking is a crucial step in preserving the quality and effervescence of your champagne. An oak cork is compressed and inserted halfway into the neck of the bottle. The cork, a sustainworthy material, then expands to form a tight seal. The wire cage, or muselet, is placed over the cork to secure it firmly in place. This not only prevents the cork from popping due to the pressure inside the bottle but also becomes a part of the champagne’s iconic presentation.

- Key steps:

- Compress and insert the cork into the bottle’s neck.

- Secure with a wire cage to prevent the cork from popping out.

Labeling and Packaging

Your bottle’s outer appearance plays a significant role in branding and customer selection. Labels provide essential information and contribute to the allure of the champagne, rosé champagne, blanc de noirs, or blanc de blancs. The label will showcase not only the brand but also the specific type of champagne enclosed. This could distinguish between luxurious vintage years or various regional varieties like cava or prosecco. Packaging often involves a protective box or wrapping that further embodies the elegance and exclusivity of the champagne.

- Key steps:

- Apply the label, indicating type and brand.

- Package the bottle to enhance visual appeal and ensure protection.

Variations and Special Processes

While the traditional method for making champagne is well-established, variations in production techniques can impart unique characteristics to the final product. You will encounter methods such as rosé champagne production that involve particular timing and blending, as well as the use of oak barrels that can add complexity and texture.

Rosé Champagne Production

To create rosé champagne, winemakers have two primary options. First, the blending method where still red wine, usually Pinot Noir, is mixed with white champagne base wines before the second fermentation. This approach helps to achieve the desired color and adds a certain berry fruitiness to the palate.

Alternatively, the saignée method involves macerating the juice with the skins of black grapes—also typically Pinot Noir—for a short period. This technique extracts both color and a richer flavor profile, yielding a more robust style of rosé wines. It’s your choice as a winemaker which process best aligns with the profile you’re aiming to create in your rosé champagne.

Using Oak Barrels

The role of oak barrels in champagne production lies in the aging process. While stainless steel tanks are commonly used for their neutrality, oak can introduce additional layers of complexity. Here’s how oak can influence your champagne:

- Aging in oak barrels can impart a subtle vanilla or toastiness, enhancing the champagne’s complexity.

- Lesser used but notable is the fermentation in oak, which may add a creamy texture and increased weight to the wine.

Oak-aging or fermentation is not suitable for all champagnes, especially those that aim to be light and fresh. However, for vintages where you seek depth and a richer mouthfeel, carefully selecting your oak regimen—considering factors like the origin of the wood or the size and age of the barrels—can significantly elevate your blanc de noirs or other styles of champagne.

Regulatory Standards and Designations

The production and labeling of champagne are governed by strict regulations to ensure authenticity and quality. You’ll learn how champagne must originate from the Champagne region and adhere to the rigorous standards set by the AOC, and explore the varying styles produced by champagne houses.

Champagne Appellation and AOC

Champagne is a distinct wine that must come from the Champagne region of France, which is critical to its terroir—the environmental factors that affect a crop’s phenotype. The Appellation d’origine contrôlée (AOC) is the French certification granted to specific geographical areas for wines and other agricultural products. To bear the name “champagne,” your bottle must not only come from the region but also meet these key AOC regulations:

- Location: The vineyards must be located within the Champagne AOC region in France.

- Grapes: Only certain grape varieties, mainly Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier, and Chardonnay, are permitted.

- Production Method: The méthode champenoise, or traditional champagne production method, is obligatory.

- Yield Control: There are strict limits on the amount of grapes harvested per hectare.

Champagne House Styles

Champagne houses, often referred to as marques, craft their distinct brands of champagne across a spectrum that includes vintage and non-vintage offerings. The style of the house influences your champagne significantly:

- Vintage Champagne: Produced from grapes harvested in a single year. Vintage champagne must age a minimum of three years before release, which allows for greater complexity and depth of flavor.

- Non-Vintage Brut: A blend of various years’ harvests, designed to maintain a consistent house style. It requires at least 15 months of aging but typically ages for 2-3 years.

By adhering to these standards and designations, champagne brands guarantee the preservation of the region’s legacy and quality that is recognized globally.

The Role of Nature and Terroir

In producing champagne, the interplay between nature and terroir is instrumental. Your understanding of how climate, soil, and vintage contribute is essential to appreciating champagne’s complexity.

Influence of Climate and Soil

The climate in Champagne, France, is temperate with a touch of continental influence; it offers the cool temperatures necessary for the slow ripening of grapes. This slow ripening is critical for developing the acidity and aromatic qualities that define champagne.

- Climate: Cool temperatures and adequate rainfall provide a balance that allows the grapes to mature with high levels of acidity while retaining freshness.

- Soil: Limestone-rich soils offer excellent drainage and contribute minerality to the grapes. The unique composition influences the taste and fizziness of the final product.

For example, the chalk in the soil reflects sunlight and provides warmth, which influences the development of the grape varieties like Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, and Pinot Meunier, used in your champagne.

The Significance of Vintages

Vintages in champagne represent the year in which the grapes were harvested and can profoundly affect the taste and quality of the champagne due to variations in weather patterns.

- Vintage Variation: A particularly hot or cold year will impact grape quality, and consequently, the champagne made in that year. Years with optimal conditions are declared as vintage and can produce champagne with exceptional character and aging potential.

- Dom Pérignon: Associated with quality vintages, Dom Pérignon only produces champagne from the best grapes of a single year, capturing the essence of that year’s nature and terroir’s influence.

By recognizing the significance of nature and terroir, you become aware of the numerous variables that contribute to the uniqueness of each bottle of champagne.

Frequently Asked Questions

In this section, you’ll find critical information regarding the intricacies of Champagne production, from the meticulous methods to the precise designation criteria.

What are the different stages involved in the Champagne production process?

The Champagne production process includes seven key stages: selecting the grapes, pressing, first fermentation, blending, second fermentation in the bottle, aging on the lees, riddling, and disgorgement with dosage.

Can you describe the traditional method used for making Champagne?

The traditional method, or Méthode Champenoise, involves a primary fermentation followed by a secondary fermentation in the bottle. This is where the wine acquires its bubbles from the trapped carbon dioxide.

What distinguishes the Champagne making process from the process of making other sparkling wines?

The Champagne process is distinct for its requirement of secondary fermentation to occur in the bottle of the same wine, in contrast to other methods which may involve carbonation or use of different bottles or tanks for secondary fermentation.

How much time is generally required for Champagne to undergo fermentation?

The initial fermentation takes a few weeks, but the complete Champagne production process, including secondary fermentation and aging, requires a minimum of 15 months for non-vintage and 3 years for vintage Champagne.

What are the specific requirements for a wine to be legally labeled as Champagne?

For a wine to be legally called Champagne, it must originate from the Champagne region of France, adhere to strict viticultural practices and production methods, and meet specific quality standards set by the Comité Champagne.

What factors influence the cost of a bottle of Champagne?

The cost of Champagne is influenced by the production method, aging duration, brand prestige, demand, and sometimes the specific vintage year, with high demand and longer aging typically driving higher prices.